Technological leaps will transform environmental governance

Reading time : 10 minutesTechnology is advancing much more rapidly than are diplomatic institutions. It will become increasingly difficult to perpetuate the “alternative facts” game, so deftly leveraged by actors in the past working to stall action on critical issues like climate change, biodiversity loss, and land degradation. In the world that’s coming, everything will be out in the open. Highly actionable data will be made available to everyone anywhere. This will create a revolution from the outside in -- everyday citizens and civil society organizations previously excluded from “blue zones” in the halls of power, will discover new superpowers to drive accountability and action with a few keystrokes. Let’s fast forward a few years and imagine how advances in these four technologies which build upon each other -- remote sensing, artificial intelligence, supercomputing, and distributed consensus -- might reshape how we think about the world and our place within it.

Right now, it’s difficult to fully grasp the ramifications of four converging technologies — remote sensing, artificial intelligence, supercomputing, and distributed consensus — and what they will mean for environmental governance in the future. When it comes to our current systems of governance, particularly structured around the three Rio conventions, we still very much live in a 1.0 world.

The activities of scientists are disconnected from the activities of diplomats and political decision-makers. The IPCC is perhaps the best science-policy interface that humanity has invented thus far — an expansive body of experts that assess and compile thousands of scientific reports, normalizing myriad complex data sets into concise summaries for decision-makers in three working groups. The whole process is laborious, taking years for an Assessment Report cycle (we’re presently completing AR6), which often synthesizes research completed years prior. Then there is a bit of a ceremonial formality during the Conference of Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), in which the Convention “recognizes” the importance of the best available science and “welcomes” the contributions of the IPCC.

There is no obligation for governments to act in accordance with the science, and many parties disagree with the science, submitting “alternative facts”. A blockbuster report from the Washington Post, analyzing greenhouse gas emissions reports from 196 countries, found that countries are grossly underreporting their total emissions, with some countries living in a “parallel universe.” The gap between reality and reporting is staggering — between 8.5 and 13.3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent gases per year, accounting for approximately one-fifth of total global emissions [1]. These faulty numbers then become the baseline for Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, which again are not legally binding.

It’s hard to imagine how such a system, which some have likened to kabuki theater [2], will be able to deliver the policy changes and funding flows needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C.

Fortunately, technology is advancing much more rapidly than are diplomatic institutions. It will become increasingly difficult to perpetuate the “alternative facts” game, so deftly leveraged by actors in the past working to stall action on critical issues like climate change, biodiversity loss, and land degradation. In the world that’s coming, everything will be out in the open. Highly actionable data will be made available to everyone anywhere. This will create a revolution from the outside in — everyday citizens and civil society organizations previously excluded from “blue zones” in the halls of power, will discover new superpowers to drive accountability and action with a few keystrokes.

Let’s fast forward a few years and imagine how advances in these four technologies which build upon each other — remote sensing, artificial intelligence, supercomputing, and distributed consensus — might reshape how we think about the world and our place within it.

When it comes to our current systems of governance, particularly structured around the three Rio conventions, we still very much live in a 1.0 world.

Karl Burkart Tweet

Remote Sensing: a million eyes on the planet

Only a few years ago my organization co-convened a workshop with leading geospatial scientists and conservation experts to discuss the possibility of creating a 10m-resolution land cover map of the entire world. At the time this seemed quite a remote possibility, but fast forward a few years, and we now have three different 10-meter land cover maps to choose from, allowing us to discern the crown of an individual tree.

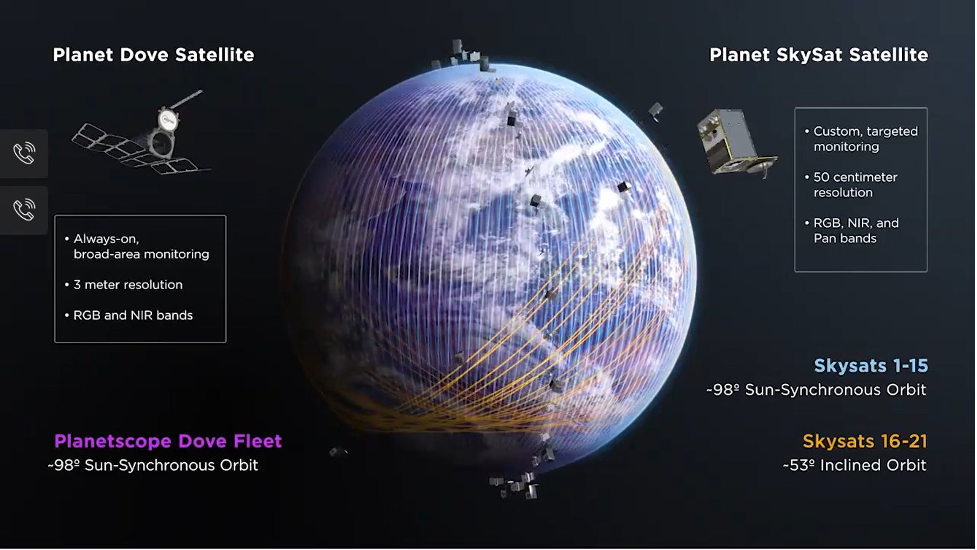

Planetscope Dove Fleet. Image courtesy of Planet, 2021.

The satellite company Planet now has an array of small Dove satellites that can take photographs at a resolution of 3-5 meters, and their Skysat solution can target locations at a 50 cm resolution. The frequency or cadence has also dramatically increased. Composite images of the Earth from space used to take months to assemble. Now the same location can be visited daily. In 2023, a new mission will launch with spectranomic sensors capable of detecting distinct chemical signatures from space, such as methane and nitrous oxide [3]. We will no longer rely upon fossil fuel companies to accurately self-report their direct emissions. Instead, we will soon be able to literally “see” methane leaks from space. A recent study found that there are 60% more emissions from industry than previously reported [4], and at COP26 world leaders pledged to cut methane emissions. These new technologies will make it possible to detect and fix these leaks.

We will have unprecedented access to daily changes in forest cover, and we will also be able to gain insights about degradation of land occurring underneath the canopy layer of a forest.

Karl Burkart Tweet

What about remote sensing of areas at night or under cloud cover? Another satellite company, Capella, is solving this problem using synthetic aperture radar, which simulates a long radio tower by emitting a variety of different radio signals to composite a detailed 3-dimensional image without the need for optical sensors [5]. This means, if a tree falls in the night, we will be able to see it. We will have unprecedented access to daily changes in forest cover, and we will also be able to gain insights about degradation of land occurring underneath the canopy layer of a forest.

Artificial Intelligence: turning data into intelligence

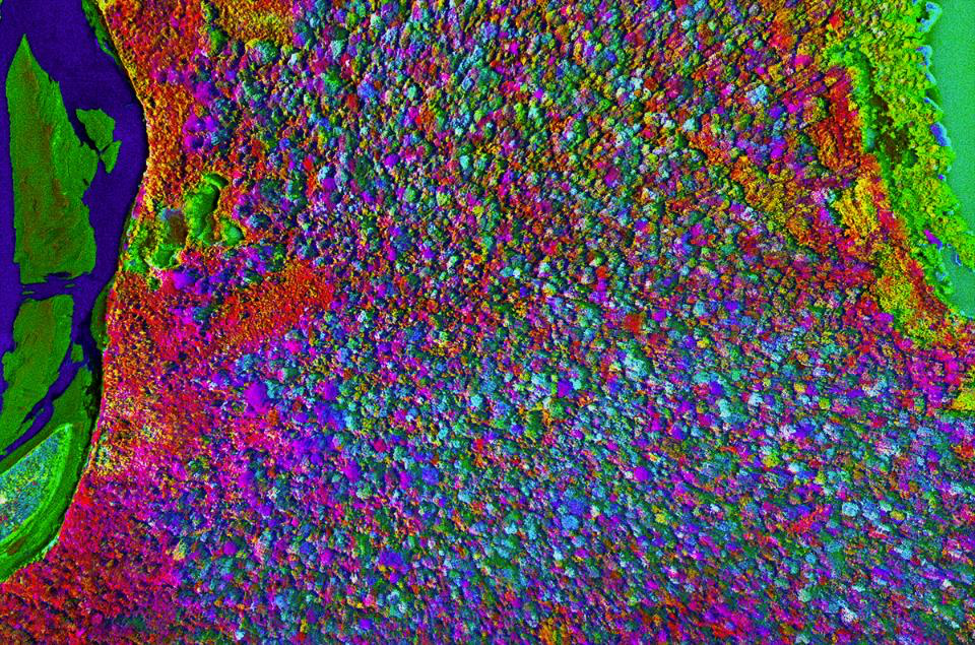

Combining advances in remote sensing with artificial intelligence we enter a new world of insights about our planet that were previously unimaginable. Spectral lidar is one such technology, pioneered by Greg Asner at Arizona State University. His team has built one of the largest libraries of tree and plant samples in the world, creating an index of chemical signatures that through machine learning algorithms can train a computer model to remotely detect distinct species from the sky. All that computer data can now be turned into a picture that shows us beta diversity, or complexity, of a forest. This results in much more precise estimates of carbon contained in the forest, but more importantly, it provides an indicator of the biodiversity present. This intelligence is vitally important for long term land use planning as the more complex the forest, generally speaking, the more resilient it will be to climate change.

Rainforest in Peru seen through the lens of spectral lidar. Courtesy of Greg Asner.

This is but one application of AI that can transform the streams of data pouring off our global satellite fleet into meaningful and actionable products that can inform how we optimize land use for a growing human population in a warming world. Already, we’ve seen applications of AI technologies to help optimize the location of crops [6] and to better understand the dynamics of surface water [7]. And of course, these technologies are not just limited to land — Global Fishing Watch developed a neural net to find meaning out of the movement of large boats on the open ocean. This created a new capability to detect both illegal fishing activity and human trafficking patterns [8].

In a world with advanced remote sensing and AI capabilities, it will be increasingly difficult for bad actors to hide.

Supercomputing: decision making on steroids

All these advances will ladder up to powerful new decision support systems (DSS), giving us mere mortals a god-like ability to ingest huge volumes of information, visualizing and modeling multiple pathways that can rapidly be compared one against another, supporting critically important decisions about the future by governments, businesses, and non-profit organizations. This is an area I have been excited about for a long time, and my organization has supported the development of several projects focusing on decision making around long-term land use and energy transition planning.

In just the past few years the speed and capability of supercomputers has increased, along with a decrease in cost. To give you an example, just 5 years ago we initiated a 2-year project with leading scientists from the Institute for Sustainable Futures at UTS and the German Aerospace Center to build a simulation of the world’s energy delivery system along with projected end use demand in hourly intervals through 2050. The project took roughly two years to complete and was published in 2019 [9]. Running an optimization for one region took 6 weeks of compute time. Today, it can be done in about 6 hours. This is a step-change in our ability to model sophisticated cost optimization scenarios to help governments and companies decarbonize the global energy supply. Multiple scenarios can be run simultaneously, creating capabilities for decision making around energy investments that were previously unimaginable.

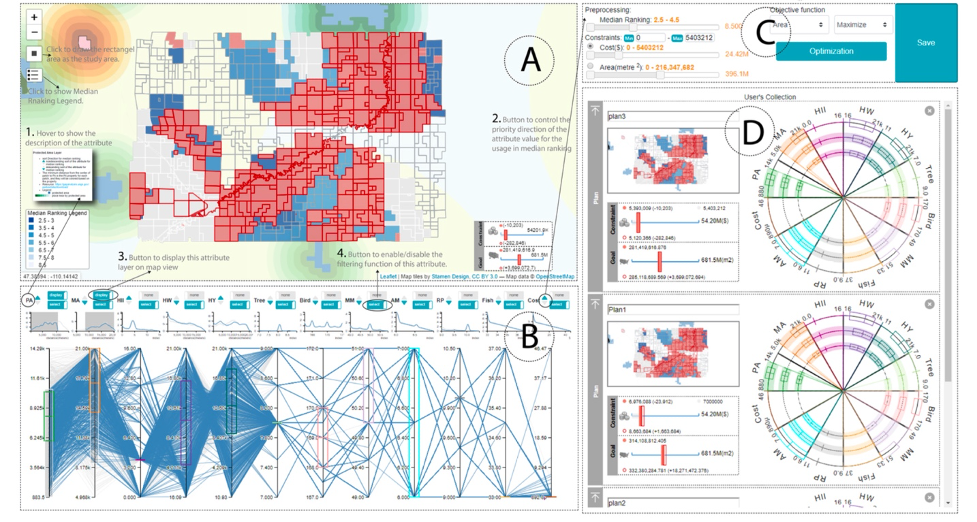

The same advancements are now benefiting sophisticated land use planning efforts. The UN Biodiversity Lab is indexing over 400 maps in one common platform [10]. How can we make sense of all these stacked data layers? Rapid advancements in supercomputing now allow a myriad of data inputs to project the relative value of land parcels. One recent effort we supported (to be published next year) builds on years of decision science to bring together data visualization, multicriteria analysis, and cost/risk optimization, enabling planners to efficiently construct, compare, and modify conservation portfolios under multiple constraints.

A Visual Analytics Framework for Conservation Planning Optimization. Zhang et al. (in review).

A parallel effort called TerrAdapt is developing a land use planning tool that goes a step farther, incorporating regional climate models to anticipate changes under various temperature rise scenarios, including the impacts of projected drought and flooding events on ecosystems and species [11]. In the forestry space, the company Vibrant Planet has developed a new technology to build three-dimensional maps for the forest floor as well as the forest canopy, enabling forest managers to predict vulnerability to forest fires and recommend interventions that can reduce the risk of fire while increasing the forest’s carbon and biodiversity potential [12]. In the agricultural space, the company Cibo Technologies, led by Bruno Basso, is putting the power of supercomputers into the hands of farmers and ranchers. Their platform pairs satellite imagery with ground sample data to build sophisticated yield models along with recommendations to optimize crop placement, reduce fertilizer use, and increase soil carbon and soil fertility [13].

This is just a handful of projects that demonstrate the new superpowers we will have in the coming years to make informed decisions by allowing our computers to ingest a mind-boggling amount of data on our behalf.

Distributed Consensus: blockchain and the rise of the DAO

Let’s briefly recap… In the very near future, we will have satellites viewing our world with breathtaking clarity; we will have leaps in artificial intelligence turning imagery into information; and supercomputing will make all that information actionable through advanced decision support systems. This will change the gameboard of global governance — making it harder for bad actors to hide while equipping good actors with the information needed to comply with multilateral, national, and subnational agreements.

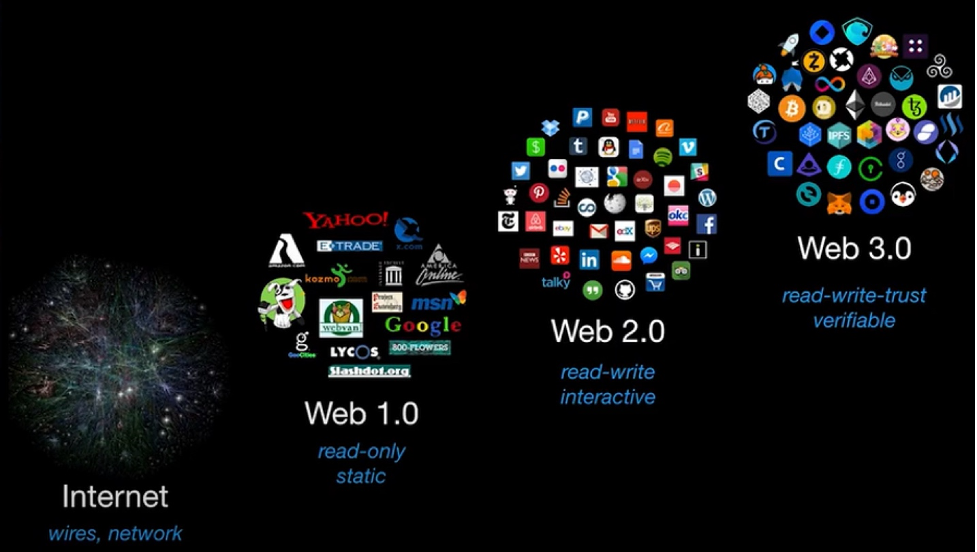

But there is a fourth revolution underway that is perhaps the most earth-shattering when it comes to global governance — blockchain technology or “Web3” as many now call it. Blockchain is, at its core, a technology that solves a vexing problem in computer science — a method to reach a common agreement in a distributed or decentralized multi-agent platform.

With the proliferation of this technology across the internet, we’ve officially left the world of Web 2.0 (an era that started around 2005). Web 2.0 allowed individuals to interact dynamically with each other online, but to do so they had to sign away their privacy to large, centralized technology companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Amazon. This resulted in huge vulnerabilities for companies, governments, and people. For example, it’s now clear the 2016 U.S. election was influenced by foreign actors via social media through a form of cyber-propaganda, a practice which continues today on major social media platforms. Facebook, under mounting pressure, recently took down a sprawling network of disinformation networks, many of which were linked to state-sponsored intelligence programs [14].

Evolution of leading logos in the evolution of the Web. Image: Protocol Labs

Web 3.0 (or “Web3”) promises to restore the original democratic ethos of the internet by taking the middleman out of the picture. Almost anything you do now on the internet — online banking, social networking, shopping, news access, even voting — will be possible without a corporate intermediary. The speed at which this transformation is occurring is stunning, especially in decentralized finance. The cryptocurrency market in the span of a few years is now worth more than the combined assets of the world’s 12 largest banks. And this is just the beginning. The implications for collective governance are even greater.

Legendary technology investor Naval Ravikant describes his reaction to first learning about the possibilities of blockchain technology:

“I read about the Byzantine General’s Problem and the solution to that, and I realized wow, you can now organize people without rulers… The Byzantine General’s Problem basically (asks), how do you get people to coordinate when no one knows each other, and nobody trusts each other… So now you can take systems that before would have to be run by centralized authorities… and can be replaced by a credible vote of all the people participating in the network…” [15]

The idea of organizing people without rulers is the central concept of the DAO — the Decentralized Autonomous Organization. There are dozens of DAOs launching daily, bringing the power of distributed consensus to every conceivable web application. Several are looking to disrupt conventional actors in the environmental space. Klima, for example, is hoarding legacy carbon offsets, taking them off the table and driving companies to purchase higher quality carbon credits [16]. FlexiDAO allows energy buyers to easily source all their energy-related data and certificates without the need for third-party processing or hardware devices — a gamechanger for companies seeking to achieve net zero energy emissions, bypassing the hurdles put in place by legacy utility companies [17].

People could now directly determine the future of their ecosystems, based on solid science presented to them in an actionable format.

Karl Burkart Tweet

In terms of the conservation of nature, one of the most challenging problems facing humanity, one can imagine a DAO that builds upon the three converging technologies described above — remote sensing, artificial intelligence, and supercomputing — by bringing stakeholders together in a particular region and empowering them with a real vote (a “governance token” in Web3 lingo) on the scenarios developed by this new technology stack. People could now directly determine the future of their ecosystems, based on solid science presented to them in an actionable format. Features like quadratic voting, which allow people to weight different options, could be compiled through distributed consensus. A complex land use decision, which previously would have taken years for community stakeholders to sort out, could be done in days. And decentralized finance could be linked to the outcome, triggered directly by a satellite observation. Individuals in the community, the true stakeholders of the project, could be paid directly through their Web3 wallets — a Universal Basic Income for Conservation scheme powered by the people.

It sounds like science fiction, but it could be just around the corner.

[3] https://www.planet.com/pulse/carbon-mapper-launches-satellite-program-to-pinpoint-methane-and-co2-super-emitters/

[6] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S258972172030012X

[7] https://www.sdg661.app/

[8] https://globalfishingwatch.org/

[9] https://oneearth.uts.edu.au/

[10] https://unbiodiversitylab.org/

[11] https://www.cascadiapartnerforum.org/terradapt

[12] https://www.vibrantplanet.net/

[13] https://www.cibotechnologies.com/

[14] https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/12/01/facebook-disinformation-report/

[15] https://tim.blog/2021/10/28/chris-dixon-naval-ravikant/

[16] https://www.klimadao.finance/

[17] https://www.flexidao.com/respring