The Escazú Agreement Contribution to Environmental Justice in Latin America: An Exploration Through the Lens of Climate Litigation

Reading time : 8 minutesThe adoption and entry into force of the Escazú Agreement marked a milestone for environmental and human rights law in Latin America. Now, its implementation begins. At the same time, climate litigation is flourishing in national jurisdictions of the region. This convergency raises an obvious question: Will the implementation of the Escazú Agreement impact the unfolding of climate litigation? If so, how? Based on interviews with Latin American litigators, we identify key Escazú’s implementation points that may contribute to climate litigation. Furthermore, we unveil the role that (climate) litigation and courts can play in the Agreement’s implementation and in processes of diffusion of good practices through the region.

It is quite a fascinating time for International Environmental Law in Latin America. The last few years have seen remarkable legal milestones, such as Advisory Opinion 23/17 of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR), the adoption (2018) and entry into force (2021) of the Escazú Agreement and the request by Colombia and Chile for an IACtHR advisory opinion on Climate Emergency and Human Rights Obligations (2023). Converging with these legal developments, climate litigation has started to flourish in national jurisdictions (Auz 2022), as it has in the Global South in general, with landmark cases and decisions of transnational interest arising and attracting ever-increasing attention (Peel and Lin 2019).

National and regional legal developments interact with each other in very interesting ways (Aguilera 2023; Medici-Colombo 2022). A foreseeable interaction is that of the Escazú Agreement with the proliferation of environmental and climate litigation in the region. Particularly, the instrumental character of Article 8 of the Escazú Agreement — which enlists several provisions containing procedural and institutional standards aimed at guaranteeing effective access to justice — for actors resorting to courts with climate concerns seems to be apparent but remains empirically uncharted. Will the (implementation of the) Escazú Agreement contribute to climate litigation? If so, how? Answering these questions and charting the thus far uncharted was precisely the aim of an article by Thays Ricarte and myself which was recently published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), as a result of an exceptional project of the Global Network for Human Rights and the Environment (GNHRE), led by Maria Antonia Tigre and Melanie Murcott with the goal of amplifying the voices of Global South scholars. This post summarises our findings.

1/ Interviewing climate litigators

To explore the interface between the implementation of the Escazú Agreement and climate (and environmental) litigation we conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 litigators involved in 15 climate cases in six Latin American jurisdictions: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador and Mexico. All of the interviewees were advocates for plaintiffs, mainly individuals, groups, or non-governmental organizations, pursuing ‘pro-climate’ interests.

The semi-structured questionnaire focused on two broad questions:

- what are the main procedural barriers faced in climate cases?

- what are your expectations that the Escazú Agreement’s implementation will overcome these barriers?

Over the first part of the interviews, discussions addressed different procedural concerns and complexities of the entire ‘litigation journey’, from the very beginning (pre-litigation stage) to post-judgment (enforcement phase). Even though the question was primarily directed to the interviewees’ climate litigation practice, their broad environmental litigation experiences inevitably informed their responses, and a clear distinction between barriers in climate litigation vis à vis environmental litigation was not observed. In that regard, a specific question was posed about the presumption that climate litigation involves higher procedural obstacles for plaintiffs than environmental litigation. Throughout the second part of the interviews, discussions focused on the interviewees’ expectations regarding the early or future implementation of the Escazú Agreement and if (and how) it could help to overcome the identified barriers. This focus was warranted given that the Escazú Agreement had only been in place for roughly a year at the time the interviews took place.

2/ Results

2.1. Procedural barriers in climate change (and environmental) litigation

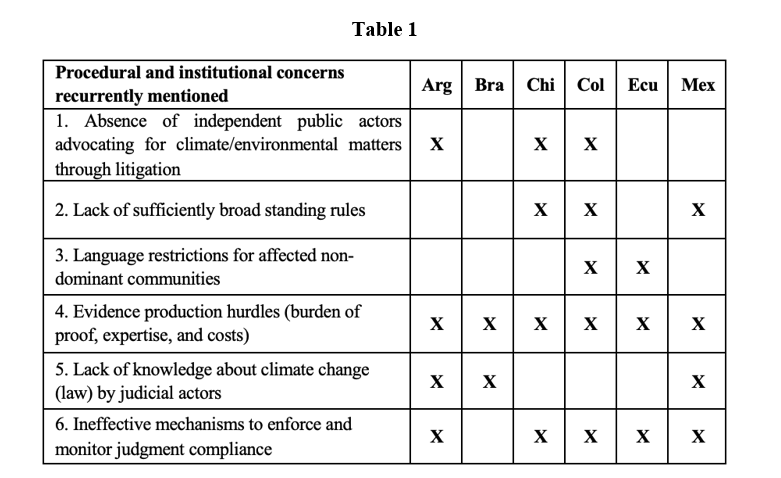

Several procedural and institutional barriers in climate and, more generally, environmental litigation were raised by the practitioners, of which six were repeatedly discussed. There is not enough space in this post to summarize all of the insights stemming from the interviews about each of these procedural/institutional concerns (full article here), but Table 1 identifies them and illustrates their distribution among jurisdictions.

Source: Medici-Colombo and Ricarte 2023

It is worth clarifying that an absence of discussion of a barrier must not be interpreted as suggesting that such a barrier is not present or was overcome in the jurisdiction, but simply that it was not a key concern of the interviewees as regards their climate and environmental litigation experience. Not only were questions not intended to obtain an all-encompassing response, but also the sample was too small to reach that conclusion.

2.2. Escazú Agreement contribution to climate (and environmental) litigation (and vice versa)

Unsurprisingly, every interviewee identified the Escazú Agreement as a more than welcome development with the ability to positively affect and reinforce access rights enforcement, including access to justice, in their jurisdictions.

Less predictable than this common positive perception were the responses regarding what they expected from its implementation. Interestingly, a dominant answer was that, instead of regulatory change, the Agreement’s implementation will mainly unfold through the intervention of courts, meaning through judicial precedents directly interpreting and applying the Agreement. In this sense, interviewees mentioned lawsuits and judgments already referring to the Escazú Agreement as a relevant legal ground, regardless of the apparent need for some regulatory or normative intermediation and even before its entry into force. In this understanding, practitioners from various jurisdictions expressed their intentions to pursue the implementation of specific standards of the Agreement through litigation, including climate litigation.

Beyond this widespread perception, some interviewees did predict regulatory intermediation to implement the Agreement. For example, one of the interviewees ventured that, in Argentina, the implementation could take place through an ongoing process of adoption of an act on collective processes, based on the Ibero-American Model Code of Collective Processes, and the enforcement of a recently enacted act (Act No. 27.592, ‘Ley Yolanda’) that requires the training of public servants in environmental matters. Remarkably, the Chilean interviewees highlighted that prospects of implementation of the Escazú Agreement in this jurisdiction would be deeply affected and defined by the results of the process of constitutional reform. They observed that the constitutional draft text was closely intertwined with the Escazú standards and included many arrangements that would allow for a straightforward implementation. The implementation process would look very different depending on the outcomes of the constitutional referendum (on 4 September 2022, Chileans voted to reject the new constitutional text).

In addition, we asked interviewees for some examples of good practices that they consider crucial for implementing the Agreement. A variety of procedural rules and arrangements were elaborated, some of which are obvious from the identified barriers (e.g., broadening standing rules, reverting the burden of proof and so on). Two good practices are worth mentioning: public hearings and environmental courts.

Public hearings, according to the interviewees, could be a valuable mechanism, among other things, to (i) introduce complex scientific evidence into cases, (ii) promote civil education through the courtroom (see e.g., PSB and Others v. Brazil (on Amazon Fund) and PSB and Others v. Brazil (on Climate Fund)), and (iii) monitor the enforcement of complex judgments (see Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment et al. in Colombia). In turn, interviewees observed that environmental courts could be instrumental to overcoming barriers such as the lack of specialized knowledge and celerity. However, at the same time, some of them were cautious with this idea due to concerns about specialized environmental courts applying law in a manner that would be too formalistic or ‘administrativy’ (attached to administrative law), which could be counterproductive.

3/ Ideas of transnational interest: a discussion

Among the many different topics that would merit attention, our paper devotes a final section to discussing three issues/ideas of transnational interest.

3.1. The implementation of the Escazú Agreement: action points and the role of litigation

In the first place, we argue that a plausible interpretation of the results would be to describe the six identified hurdles (Table 1) as action points that require attention in the context of the implementation of the Escazú Agreement. Particularly, hurdles related to evidence production and judgment enforcement and monitoring seem to be of widespread concern throughout the region. The interviews’ results not only point to those barriers but also offer some nuances about their causes and possible mechanisms to overcome them.

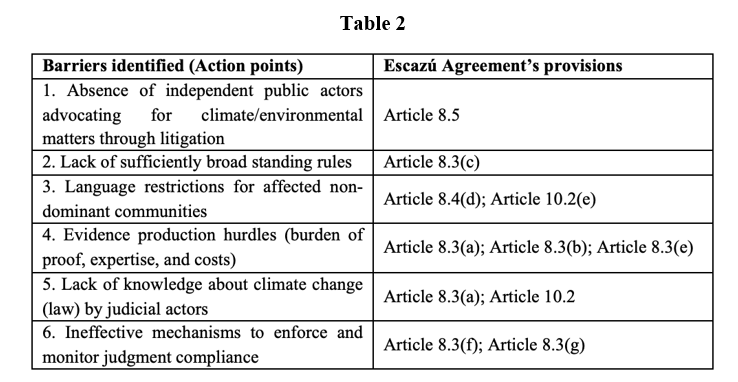

Notably, as Table 2 shows, the Escazú Agreement includes standards regarding all the identified procedural and institutional barriers. This speaks to the wide-ranging approach taken by the negotiators of the Agreement and the opportunity to address the barriers directly through its implementation, both through its institutional framework (COP and the Committee to Support Compliance and Implementation) and at the national level.

Source: Medici-Colombo and Ricarte 2023

National implementation can vary between jurisdictions according to the rules governing the incorporation of international law and the hierarchy within domestic legal orders. Auz (2022) has emphasized that most Latin American States are monist and treat international law as being equivalent to domestic law and therefore as being directly enforceable in domestic courts and has described this porosity as an important feature contributing to climate litigation. This was confirmed by some of the interviewees who recognized that the Agreement directly occupies a high level in the normative pyramid of their jurisdictions.

That explains, at least partly, one of the remarkable insights of the results: the interviewees’ widespread expectation about the relevant role that courts will play in the implementation of the Escazú Agreement, even surpassing regulatory action. This points to a significant contribution not only of the Escazú Agreement to the prospects of litigation, but also of litigation for the effective implementation of the Agreement. In this sense, legal practitioners, rather than mere receptors of standards, are active players in its implementation and development by proposing in their cases that courts re-interpret and adjust domestic law, theories and practices.

3.2. Hurdles in climate litigation: standing rules

A second issue is that of standing rules as a particularly problematic barrier for climate litigation in the region and the possibility of overcoming it through the Escazú’s implementation.

Chilean and Mexican practitioners observed that the special features of climate change make it very difficult to justify standing for actors who must prove to be distinguishably or uniquely affected. The consequences of this barrier are not trivial but substantial and affect not only the entrance to the judicial process but also how that entrance is made possible. In Mexico, communities are obliged to appeal to NGOs mostly situated in the capital and not always available to engage in a case of this kind. In Chile, plaintiffs who want to claim for climate damages (for example GHG emissions or climate change-induced damages) have to seek alternative environmental arguments (to comply with the theory of the ‘adjacent environment’) to get access to the judicial process, limiting climate litigation strategies and precluding the possibility of obtaining a pure climate precedent.

Remarkably, this barrier has also been highlighted by Kelleher (2021) regarding ‘systemic climate litigation’ in jurisdictions of (European) Parties of the Aarhus Convention. As Kelleher does with the Aarhus Convention, we believe that a purposive and consistent application of the Escazú Agreement should resolve the standing conflict posed by climate change in an affirmative manner. However, the decision by the Mexican Supreme Court in Julia Habana et al. v. Mexico casts doubt on that prospect, with the Court failing to engage (at least not expressly in its judgment) with any provision of the Escazú Agreement.

3.3. Good practices and the ‘transnationalization’ of procedural law through the Escazú Agreement and climate litigation

A final novel idea sketched by the paper is that of the ‘transnationalization’ of good practices (here procedural rules or arrangements) based on the implementation of the Escazú Agreement and the role of (climate) litigation.

According to this idea, thanks to the dual (internal and external-regional) and entangled nature of the process of implementation and development of the Escazú Agreement, practices that prove to be useful to overcoming procedural hurdles within one jurisdiction (e.g., reversal of the burden of proof in Ecuador) leave behind their entirely domestic nature to become elements of transnational interest, apt to be involved in legal diffusion between jurisdictions.

Considering that, as noted by the interviewees, litigation is directly involved in the implementation of the Agreement, the ‘transnationalization’ implies that it could make perfect sense for Latin American climate litigators to begin pointing in their lawsuits to beneficial procedural standards from other jurisdictions in order to guarantee effective access to justice under the auspices of the Escazú Agreement.